She had turned

her dressing table into a shrine and it broke my heart to see; there were

photographs, postcards, letters, jewelry, trinkets, and all the bric-a-brac of

romance. Two years after Paul’s death and she was still in mourning. The flat

they once shared was a mausoleum to his memory; unchanged since that fateful

day.

I once fostered hopes that she might turn to me after a suitable term of grieving, but I had become that most pitiable of species – the best friend. I longed to tell her how I felt, but I dared not because I knew she would be horrified. She trusted me and I felt that at some basic level my love was a betrayal of that trust. My love for her was just another of my guilty secrets and something best left unspoken.

When she told

me she needed a hand sorting out old clothes for some charity shop I briefly

hoped that she had begun to clear out some of Paul’s old things; that she had

perhaps started to move on. When I got to the flat, however, I discovered that

it was her own clothes she was throwing out. Looking at the assorted jumble of

clothing I wondered if she was not divesting herself of the last remnants of

colour in her life.

“Thanks for coming around Pete, I really appreciate it.”

“No problem Marie; anything I can do to help...”

"There’s bound to be better things you could be doing on a Friday evening.”

“Not really – unless you count my busy TV schedule.”

“You need a girlfriend.”

“You’re probably right.”

There followed an excruciatingly embarrassed silence which lasted a heartbeat, but which filled an eternity. She had taken to these pronouncements lately and I had never formulated a decent retort. I should have found a girlfriend and gotten on with my life, but it was already too late. Paul’s death wrecked both our lives and we orbited each other at a discretionary distance – both of us alone in our private grief.

After dropping the clothes of at the charity shop she invited me back to the flat for a coffee. I was hoping she would. We wound our way up the tight concrete stairwell and I recalled the nightmare of hauling their furniture up those steps – Paul and I heaving and cursing with every footfall. But we were laughing too; those were happier times, before he got ill and dragged us all into hell with him. On the top landing to the right of the flat was the door that lead to the roof – it was padlocked now, but that did not stop the memories from flooding back each time I saw it.

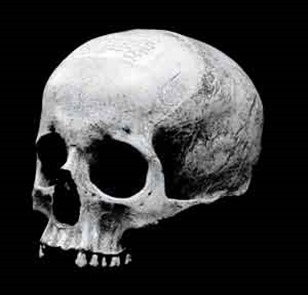

Paul had been an outgoing and vivacious character and was always the first to see the funny side. He was the perennial joker and the life and soul of any gathering, but Paul began to change. He threw malevolent tantrums and sulked in deep depressive funks which were counterpoised with manic highs when he lost all sense of propriety. Marie nearly left him then, but when he was diagnosed with Bi-Polar Disorder she thought her place was by his side fighting his dreadful affliction.

That day Marie had called me and asked if I could pop by and check on Paul because she would be delayed at work and he was not answering the phone. He was prone to ignoring the phone, so there was nothing untoward in that, but she worried nonetheless. When I got to the flat there was no answer, but the door was unlocked so I went inside. There was no sign of Paul, but his typewriter was on the kitchen table and initially, I was glad to see that he had been writing again.

A man acquainted with sorrow,

weary of the

world, tired of life,

has no faith

in tomorrow,

no taste for

endless strife,

sorrow rules

his heart,

and measures

every beat,

tears his soul

apart,

and turns his

flesh to meat.

It seemed such a sad hymnal that it gave me a chill inside. My friend was fighting for his life and I was impotent in the struggle. He was not in the flat, but I knew where he would be – I found him on the roof watching the traffic flow by below.

“Hey, Paul – how you doing?”

“As well as can be expected.”

“You writing?”

“Only obituaries.”

It was so hard to reach him sometimes – every inquiry only threw up negative responses and sometimes they were chilling. I really felt sorry for Marie. She had to deal with his blank numb ripostes and his suicidal ideation. I could see it was crushing her spirit, but Paul did not seem to notice, he seemed on a track of his own and oblivious to the world around him.

“Well that’s something – at least you are writing.” I smiled hopefully.

“It’s pointless.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Everything we do is pointless. We steal our days while we fend off the inevitable. I just wish it was over.”

I don’t know what came over me. I was angry with him, frustrated by him. I’d had enough. I charged into him and gave him a hard shove. He toppled over the side of the building and landed with a sickening thud. My only thoughts then were that I hoped he was dead and that no one had seen me.