We ran

and ran until our legs would carry us no more – our pursuers had stopped

chasing us a mile back – but we were running for the joy of it. We were gasping

and panting for breath as we laughed uncontrollably. I thought I might

asphyxiate from laughter. I tried to speak to Bell, but could only muster some

wheezy vowel sounds. He was on the ground now in paroxysms of mirth.

“I think the whole pub was chasing us!” I

exclaimed - once I’d caught my breath.

“It might have been something that I said,” replied

Bell.

We

went into convulsions of laughter once more; he laughed the way I imagine

coyotes laugh with sniggers and whimpers and howls. It was typical of Bell that

after a few drinks his impulse control completely deserted him. We were on a

pub crawl down Leith Walk and went into the Central on a dare. It was the

roughest pub on the Walk in those days. I would never have gone in there

normally, but Bell urged me on. The place was mobbed, but Bell managed to grab

a tiny space on a bench next to this middle aged bird, to tell the truth she was

quite tasty. She and Bell were soon wrapped in conversation, her husband who

was sat next to her kept a leery eye on proceedings. Then it happened – I knew

it would. Bell had to push things too far.

“You make a handsome couple” he said.

“Thank you” she replied flush of face.

“Any chance of a wee kiss?” he

enquired lecherously.

“Oh, no” she answered shyly.

“Just a wee peck maybe?” he insisted gently.

“Oh, alright then” she puckered her lips.

“Oh, no you hen – I mean yer man” the

company went quiet and her man glowered at Bell. We split laughing and I broke

into a run with Bell trailing behind. Sure enough a crowd of tough looking

radges followed us from the pub.

“Do you all want a kiss?” taunted Bell as I dragged

him away.

“You have to stop antagonising the heterosexual community

Bell –

before you get your head kicked in” I warned him.

“You know the difference between straight and queer Johnny?” he

asked.

“Enlighten me Bell.”

“Six pints of lager.”

“I only drink special.” I quipped.

“Maybe you never gave lager a chance.”

That

last comment hung in the air between us and we let it die there. We were headed

back to my place and a fridge full of beer when Bell suggested we make a

detour.

“Let’s go wind up Buddha. I could use a line of speed.”

“Okay, but go easy on him. He’s a good mate of mine.”

“I don’t know what you mean.” replied Bell; “I’m

a perfect gentleman around your friends.”

I

rolled my eyes, but said nothing. Bell seemed contemptuous of anything straight

and his behaviour around my hetro friends was often a bone of contention

between us. We arrived at Buddha’s place and made our way up the three flights

to his flat. Buddha seemed glad to see me, but was a little more reserved

toward Bell.

“Come in lads and take a pew. Anyone fancy a cup o’ chai?”

Once

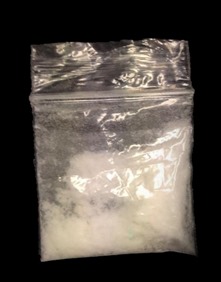

the tea ceremonial was dispensed with Buddha set about sorting out three

generous lines. He assured us that this gear was the bee’s knees and that we’d

be flying in no time at all.

“Ye’ll be rabbitin’ awe night wi this stuff – guaranteed.”

“You only serve the best Buddha,” replied

Bell; “That’s why you’re my favourite pusher.”

Bell

had that glint in his eyes. He was out to provoke Buddha who bristled at the

word ‘pusher’.

“I’m nae pusher – get that straight. I never pushed anything on

anybody in my life. My clientele don’t need pushin’ they jump o’ their own

accord. I’m a dealer and a bloody good wan. I deal in entertainment of the

highest quality and have never had any complaints. My deals are spot on and my

gear is clean, never trod on. People are never pushed in my direction – in fact

I never heard of anyone being pushed into takin’ drugs – it’s always been on a

strictly voluntary basis. Take yer average junkie – naebody forces them into

it. Yer junkie gets up every morning and decides that today he’ll be a junkie

an’ he’ll be a fuckin’ junkie til he changes his mind. That’s what separates

the casual user from the addict – greed and will power. Naebody makes them

junkies – they jump o’ their own accord.”

I

agreed wholeheartedly with what Buddha said; though I thought there was a

certain irony in his saying it. Buddha had been doing speed for ten years or

more and as far as I knew he did it every day. We snorted our lines and snorted

some more; sure enough we were talking and philosophising into the small hours

and beyond the dawn.

“You like it then?” asked Buddha.

“Aye we like it alright – its rocket fuel.” I

replied.

“I could do you a lay on” he offered.

“I don’t know...”

“Take a couple of ounces – pay me next week – ye can flog it at a

tidy profit and still have a bit for yersels.”

And

so I left Buddha’s with two ounces of pure amphetamine sulphate and an ounce of

sticky black hash in my pocket. Had I been pushed into it? No, I think I

jumped, with a little persuasion.

“Well, where are we goin’ now?” enquired Bell.

“Back to my place,” I replied, “I just

want to put my feet up and relax.”

“Let’s go for a drink,” suggested Bell.

“It’s six in the morning Bell.”

“I know a place that opens at six”

“I suppose I could use a bite to eat to settle my stomach.”

“Fuck that – I’m buying you six pints of lager!”